For years I have emphasized the national significance of Fort Shaw, Montana, often to deaf ears it seems. But just stop and think: at this one place in the valley you have centuries of Native American history, then immediately after the Civil War comes the federal presence with the establishment of Fort Shaw in 1867. The last regiment serving at Fort Shaw were four companies from the 25th U.S. Infantry, an all African American unit, with the troops often called Buffalo soldiers. Once the military left the post in 1891 another federal program through the Interior department created the Indian Industrial Boarding School that operated 1892-1910. By that time the U.S. Reclamation Service already had launched the massive Sun River Irrigation Project, which created the infrastructure that shapes the valley today, designating the Fort Shaw district as its initial project. So much change in less than 50 years. Whew!

Telling this huge story has largely been left to the Sun River Historical Society. I first met the group when I did a public meeting at Fort Shaw during the 1984 state historic preservation planning process. The society’s vision then was huge—but over two generations the members have met, even exceeded, that vision. In this post I want to highlight the efforts of the society and Blackfeet Nation in restoring the Fort Shaw Military Cemetery.

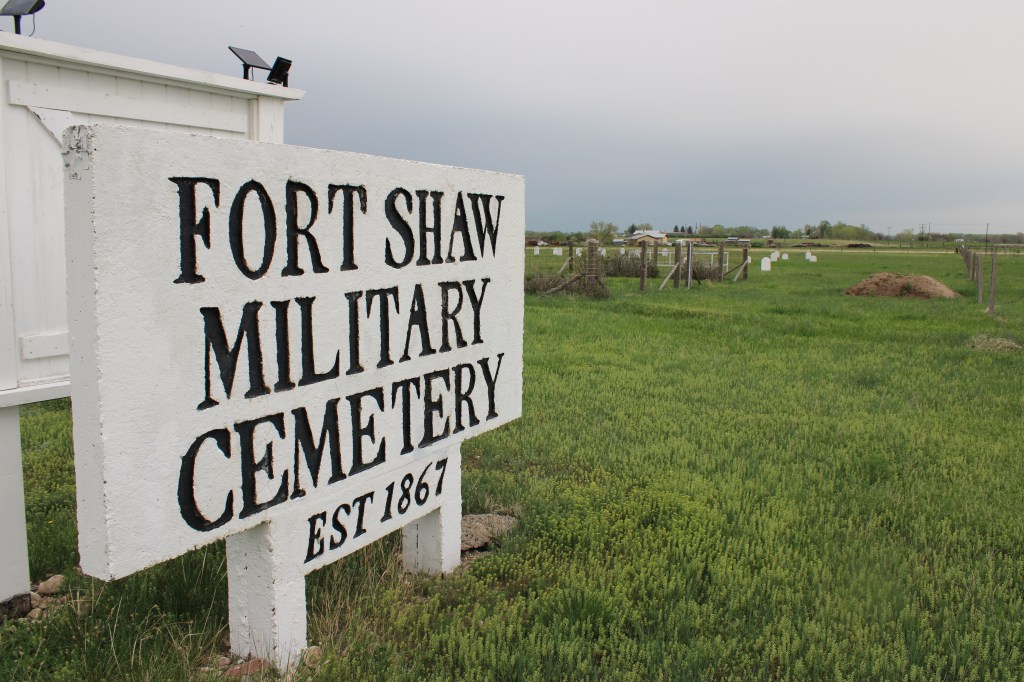

The cemetery is on a graveled county road on land managed by the federal Bureau of Land Management.

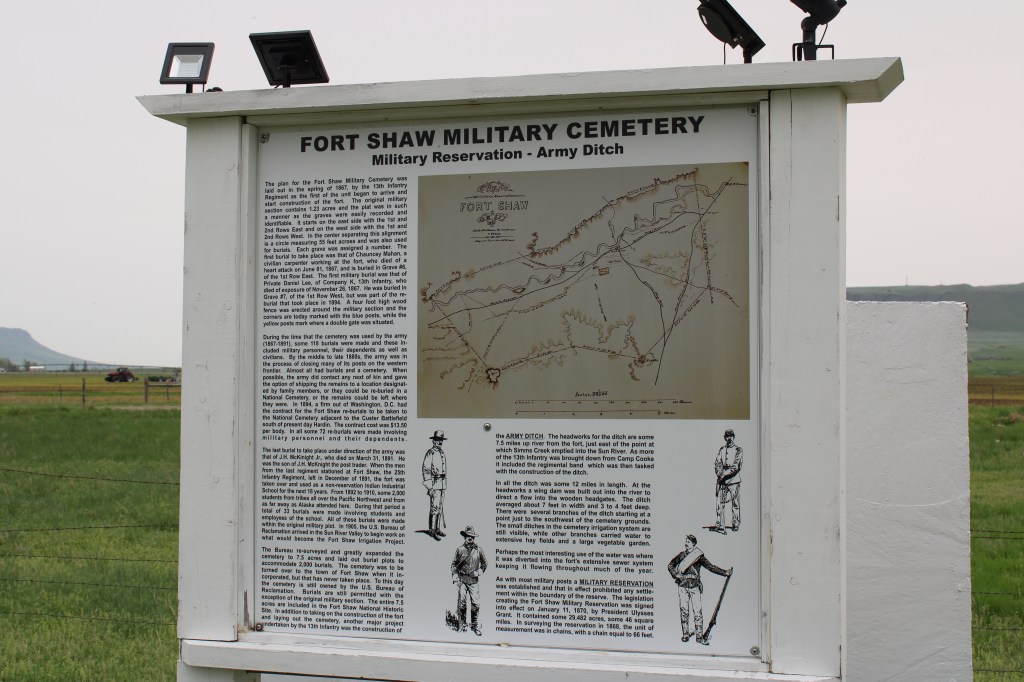

At the time of the historic preservation survey the cemetery was known but not well maintained. There were some extant grave markers but many more grave depressions that marked lost tombstones or removed graves.

The U.S. Army, after closing the fort, had decided to remove the soldiers from the military cemetery. In 1894 that process began and 74 soldiers, fort employees, and family members were moved from Fort Shaw to either family cemeteries or to Custer Military Cemetery at the Little Big Horn Battlefield.

Seven soldiers remained buried at Fort Shaw; eventually the standardized military tombstone marked their graves.

In 2016 Dick Thoroughman (who has since sadly passed away) convinced his fellow society members that they could restore the cemetery and restore a sense of dignity to those buried there by “saying their names.” The society built replica tombstones and then placed a small insert that gave the name and identification of the deceased

Among the marked graves are thirty-three students from the Indian Industrial Boarding School. Each tombstone is a testament to the horrors of the boarding school program. The names are not just of Blackfeet children but from many nations in the West and Alaska.

The federal boarding school program ripped children from their families, isolating them at the schools where their teachers too often literally tried to beat native culture and identity out of the students. Almost 2000 Native American children attended the Fort Shaw school from 1892-1910. Tribal members today believe that there might well be more than 33 Native American children buried at Fort Shaw.

Blackfeet Nation members have held vigils at the cemetery for years to honor and remember the victims of the boarding school. As Christine Diindiisi McCleave of the Native American Boarding school Healing Coalition told the University of Montana’s Byline Magazine, “We are in a moment of history where the wound of unresolved grief from Indian boarding schools is being ripped wide open. The truth is being unearthed and yet so much more is still unknown .”

The Sun River Historical Society recently restored the commanding officers house in 2019, where they are trying to find out more on the life of “Chinaman Joe” who worked as a domestic and is also buried at the cemetery (see below).

Many, many stories are yet to be identified, researched, and interpreted at this 7.5 acre property. But the 2016-17 restoration started the process. The Sun River Historical Society has earned thanks for their commitment and dedication to the task.

Excellent field work, Carroll! I will add Fort Shaw to my next visit through Montana. Everyone should visit Montana at least once, (I tell anyone who will listen…).

I’ve had a life long interest in history, and perhaps not coincidentally, our son Barrie Ryne Blatchford is graduating from Columbia University later this month with a PhD in environmental history. His dissertation deals with the impact of foreign species introduced into North America largely in the late 19th century. He argues that historians have not fully grasped the significance of that activity socially, economically, or on the environments these species were introduced. Coming one day to a bookstore near you, I’m sure.

Cheers,

James Blatchford

Maple Ridge, BC

I recently learned that a great grand aunt who attended the Indian school is buried in the cemetery. Annie Koon (Kuhn) was nine years old when she was registered at Fort Shaw in October 1898. She contracted rheumatic fever barely a month after arriving and passed only days later. I am convinced that the separation from her family and homesickness were major factors in succumbing to illness.

I am extremely grateful to the generous souls who have restored the graves at the cemetery. Your act of kindness is not only appreciated, it is an inspiring example for all to follow. Thank you.